Surveying Seismic Shifts: KBR Engineers Trek to the South Pole

Forget cars, have you ever ridden to work on a snowmobile?

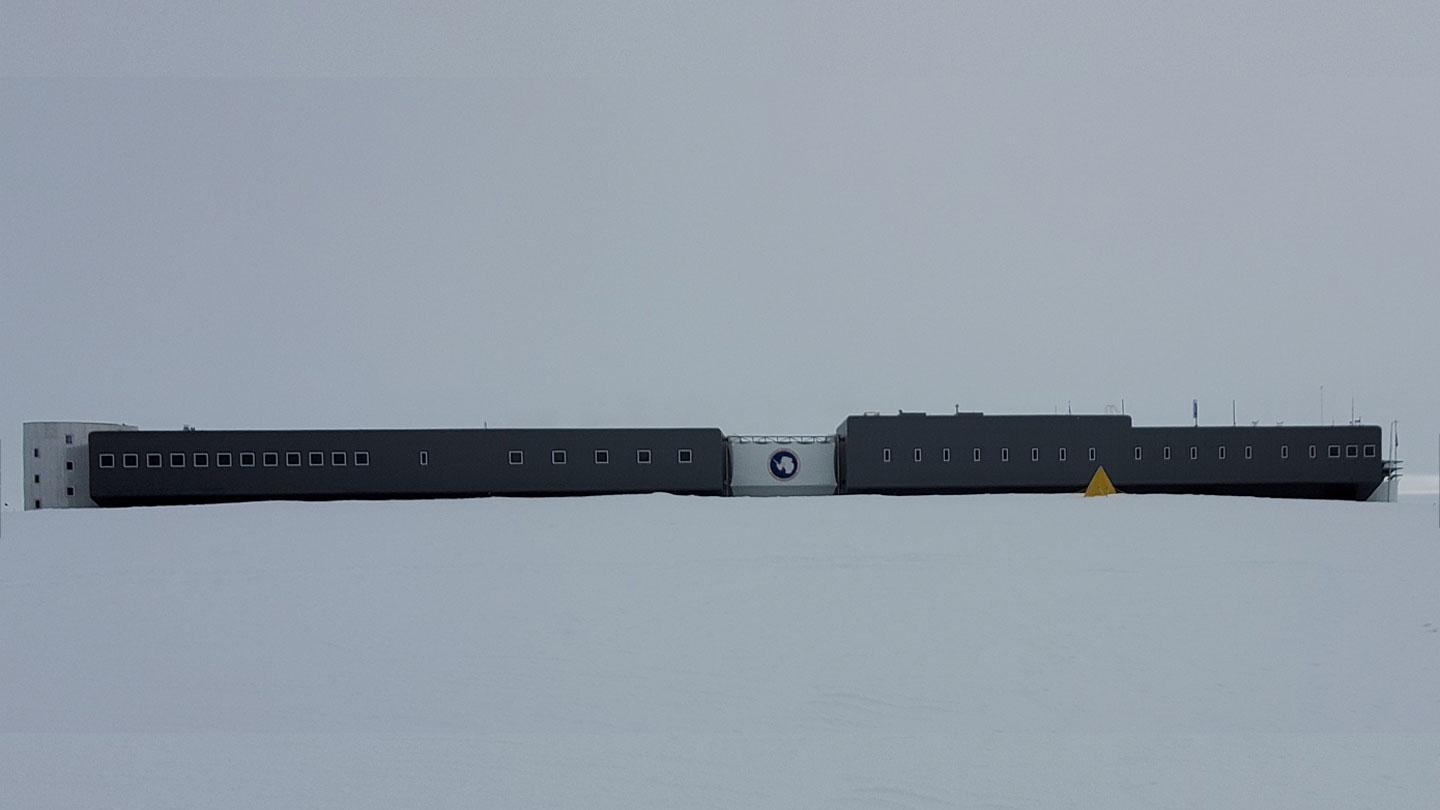

Take a second to imagine traveling to the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station (ASSPS) in Antarctica, a remote U.S. scientific research post and the southernmost place of human habitation on the Earth – not to mention your home for the next week or two.

Once you arrive, it’s negative 50 degrees Fahrenheit outside. You’re on your way to provide technical and maintenance support services to the seismic observatory South Pole Station (QSPA), five long, bitter miles away from ASSPS.

Dressed head-to-toe in heavy work apparel and cold-weather accessories, you venture out into the dry, polar expanse hoping your extremities stay warm long enough for you to get to the next heated shelter for some quick defrosting between projects.

For KBR seismic field engineers, Gilbert Vallo and Kyle Jones, this is just another day in the life of maintaining the U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) portion of the Global Seismographic Network (GSN), a high-quality, permanent digital network of seismological and geophysical sensors connected by a telecommunications system throughout nearly 80 countries with more than 150 seismograph stations around the globe.

KBR has supported USGS seismic networks for more than 35 years through periodic government contracts at the USGS Albuquerque Seismological Laboratory (ASL).

Station installation locations are selected to provide the best global coverage possible. They utilize extremely sensitive instrumentation that operate both above ground and deep underground, and require a quiet noise floor, which is why many are located in secluded parts of the world far from civilization. The stations serve as multi-use scientific facilities and societal resources for various forms of Earth monitoring, research and education.

Uniquely, this work often requires multifaceted expertise in both electrical and mechanical systems, as well as recurrent travel and hands-on labor. Vallo and Jones’ assignments frequently send them abroad to engage with many different nations and people.

“We usually visit four to seven countries a year. With most of the stations being in isolated areas away from cultural noise. We’ve gone everywhere from the desert to the middle of a jungle, in a cave, or on an island. It’s a job like no other,” Vallo said.

Much of the real-time data collected through the GSN sensors are used to assess seismic threats, massive vibrations of the Earth and its crust, as well as ground-failure hazards on regional, national and international scales. Information is then transmitted to monitoring hubs for earthquakes, volcanos, tsunamis, landslides, nuclear weapons testing and more, where data is used for rapid response and research.

KBR personnel working on GSN operations are responsible for installation, maintenance, repair, modification and supply of all foreign and a few domestic seismograph stations supported by the ASL.

In mid-January, Vallo and Jones both trekked to the South Pole for the first time in their careers. To get to the South Pole, they utilized a military LC-130 aircraft instead of commercial air. The use of specialized transportation is one of the biggest differences in deploying to the South Pole versus other areas of the world, in addition to the vast amount of extra clothing and gear.

During their visit, the pair worked to perform typical routine maintenance, which included ensuring station equipment was functioning well, and firmware and configurations were up to date. The engineers also installed new equipment and surveyed the station to forecast problems that may disrupt data collection or data flow.

Weather plays a significant role in maintaining these seismic stations, especially at the South Pole. “We found GPS antennas that had been buried over time with snow and put a strain on the outside data lines,” Vallo said, which they cleared off and replaced.

“Our primary goal of this trip was the installation of a new seismometer that is fully rated for the negative 50 degrees temperature of the seismic vault, where it is stored,” Jones said. “This state-of-the-art, long-period broadband instrument is buried below the surface to reduce noise.”

Traveling to and from the seismic station on snowmobiles and transporting equipment in a PistenBully – a vehicle with traction-enhanced wheel tread – the pair wore heavy gear to cover all bare skin to prevent freezing or frost bite. At QSPA, altitude sickness was also a concern, as the South Pole is about 10,000 feet above sea level.

“We had to look out for each other to make sure Kyle and I stayed warm and kept hydrated,” Vallo said. “The average temperature was negative 40 degrees while working outside. The South Pole is very cold and more so when you add the wind chill. The humidity is near 0 percent, so breathing in the cold, dry air made it uncomfortable, which we never got used to.”

“Working in the heavy jackets made it difficult to move around, but was needed to keep warm. We couldn’t exert ourselves too much either or we would sweat, and in turn the sweat would quickly draw away our body heat,” Vallo continued. “We also wore goggles for eye protection and to help prevent snow blindness. Although the goggles helped, they restricted our vision, so we had to mind our movements.”

Jones agreed that the below-freezing temperatures crept up quicker than expected, and appropriate cold-weather training was extremely important to successfully and safely perform their duties.

“First your feet get a little cold and circulation drops, then the chemical boot warmer stops working, and before you know it, your feet are literally freezing cold,” Jones said. “It takes a long time for the insulated boots to warm back up, so we frequently had to take shelter inside to warm up our feet or hands.”

Despite the frigid weather, Jones and Vallo successfully completed their tasks, which played an invaluable role in KBR’s quest to help USGS decipher Earth’s natural hazards, prepare for weather disasters and protect its inhabitants – all of us.

“With the seismic and other sensors becoming more advanced and providing additional usable data, our work helps the scientific community to better understand our planet,” Vallo said. “And that’s a great feeling.”